Assessing Ourselves

This case comes from a community health nurse in Maryland. It involved an outbreak among immigrants working at a tomato packing plant in a rural county.

One late spring afternoon, the tuberculosis (TB) control program in our largely rural Maryland county health department received a call from the infection control nurse at a local hospital. A 24 year old Hispanic woman, Carmen, was admitted to their hospital with cavitary TB a week earlier. We did not know Carmen, but as nurses at the county health department, we knew many of her neighbors and co-workers. We called our Spanish interpreter and arranged to go together to interview Carmen the next morning. Thus began a TB contact investigation that would take the next 18 months to complete.

The Maryland team

Carmen

Carmen was a recent immigrant from Guerrero, Mexico, and worked in a tomato packing plant in our county. She, her husband, and their two young children shared a rented mobile home with another immigrant family. Her first language was Mixteco, an indigenous language prominent in southern Mexico, and she also understood basic Spanish. Carmen had been ill for several weeks, had lost a lot of weight, and was very anxious and fearful. She was concerned about her physical state but even more worried about how the course of TB treatment would impact her family. Her communication with her medical team had been limited, as an interpreter was not always available. Additionally, the physician was new and unfamiliar with managing TB disease. Due to language barriers and misinformation, Carmen believed she could not see her young children during the 6 months of her treatment. She did not know when she might return to work and was worried her family would become homeless without her income. Isolated in her negative pressure room with no family, unfamiliar food, and nothing to occupy her attention, Carmen was close to despair.

While we couldn’t relieve her immediate symptoms, we could allay some of her fears through the interpreter. Our goal was to empower her to take care of herself so she could be discharged from the hospital quickly. We explained that before they could discharge her, the doctors would have to see her physical condition stabilized; she would need adequate housing and we would have to evaluate her family for TB. When we pointed out she could do a lot to help achieve these steps, she became more actively engaged in planning for her treatment. She promised to try to eat more and asked for specific dishes from her family and friends.

We learned she liked to sew, and bought her sewing supplies. We also asked the hospital staff to turn on her television and arranged for her to receive outside food. Our interpreter, who had longstanding ties to the immigrant communities in our county, gave her names of agencies and other resources to help her family while she was hospitalized. These small interventions helped establish our role as advocates on Carmen’s behalf, and facilitated trust between us. That trust was necessary to get through the many challenges that lay ahead.

Carmen’s most pressing concern was the daily care of her children, since her husband couldn’t leave work, and it was hard for him to go grocery shopping. We assured her we could bring a small supply of diapers and formula to the house when we evaluated her household contacts. Finally, we tackled the issue of finding housing for her family. Our interpreter worked with us to help Carmen think about which neighborhood was the most convenient for her family. Our staff brainstormed about which landlords we might approach within the next few weeks.

Our evaluation of Carmen’s household found that her three close adult contacts, her husband and the couple who shared their living space, all had positive TSTs. TB disease was ruled out in each case. Two adult contacts started treatment, and the third was found to be pregnant so treatment was delayed. One of the children was subsequently diagnosed with TB disease. During this initial evaluation period we cultivated our relationship with Carmen’s husband, knowing his support and collaboration would be essential to her recovery and completion of treatment. Indeed, the family faced numerous challenges throughout their treatment for TB and LTBI.

We understood many of the barriers that families like Carmen’s faced and had a strong network of resources to facilitate immigrants’ engagement in health care. We felt confident we could support the family through their treatment. However, the contact investigation that developed around Carmen’s case stretched our program’s competencies and resources in new ways, as we had to see not one patient or family but dozens of patients with multiple challenges through a lengthy course of LTBI treatment. In order to accomplish this, our department had to mobilize new resources and develop innovative programmatic responses to our patients’ needs.

Taking Skin Testing Outside

The first step was to ensure we had adequate staff for such a massive effort. We offered a refresher TST training and practiced on each other until our skills were up to standard. Second, we reviewed our TB skin testing tool and revised it for the plant workers. We knew some staff would have trouble understanding and accurately recording the Spanish system of two surnames, so we used a numbering system as a primary identification, and prepared cards with ID numbers to give to those tested. We also prepared instructions in basic Spanish for people receiving a TST. Finally, we tackled the question of space. Using the lunch area would be too disruptive. Eventually we realized a grassy area on the side of the building was the only feasible area because we could set up multiple stations that were spaced out enough for people to ask questions privately.

Spring had given way to summer and testing day dawned hot. We reviewed procedures with the manager and our staff was ready. Despite the heat, crowding and inevitable waiting, the atmosphere in the yard was energetic and friendly. The workers could see we had made extraordinary efforts to accommodate them and they appreciated both our attention and the opportunity to interact in their own language. We adjusted our procedures as the day went on. For example, many people tested did not know their exact birthday, so we accepted approximations (month and year without day). Several people were unable to give their exact address, so we coached them to record the name of their street and bring it when they returned to have their skin test read. We returned two days later to read the tests. We identified 81people with positive TSTs. Two had symptoms of TB; we immediately escorted them for chest X-rays and further evaluation. We educated the others with positive TSTs about further testing to rule out disease and the benefits of treatment for LTBI.

Mobilizing Our Clinic

The testing was a success and the plant manager was please the work flow was not affected. Seeing the workers viewed us positively, he was willing to accommodate our follow up of the workers with positive TSTs and again allowed us to use vacant office space as a temporary examination room.

This was more complex than the initial testing. We had to ensure quality care and maintain patient confidentiality in an efficient and non-disruptive manner. We assembled two portable stations for vital signs and phlebotomy just outside the building and close to the exam room. We brainstormed how to outfit the exam room and eventually decided to use an ambulance stretcher borrowed from the local fire department’s emergency response team. We adapted our forms to facilitate taking patient histories in a short time. We practiced with our interpreters once we had everything on a single page.

While several TST positive workers did not return to work, we evaluated the rest in our makeshift exam room during their lunch, breaks and at the end of their shifts. Four women were identified as pregnant, so we referred them to our prenatal services, and decided not to recommend they start treatment for LTBI. The remaining 69 workers were offered LTBI treatment and all accepted.

Support for Treatment Adherence

We knew continuing to use the worksite for follow-up could tax the manager’s willingness to work with us. Instead, we followed-up with patients just outside their eating area during lunch. We wanted to maintain our presence at the site as the two symptomatic patients were being treated for suspected TB, eventually bringing our cases up to four. We were in the midst of an outbreak; for us to respond effectively, regular contact with the workers was essential.

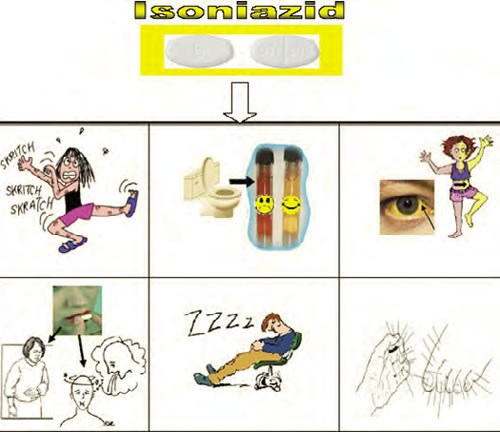

We examined all possible approaches to supporting adherence. Education was of utmost importance. Most of our patients had never heard of LTBI or the rationale for treating it. Again our interpreter came to the rescue, infusing the Spanish version of our counseling and education sessions with energetic interaction and a real desire to communicate key ideas. We had some materials about LTBI treatment side effects in Spanish, but they would not be helpful if patients did not know Spanish or had very low literacy levels. We worked with our interpreters and designed pictographs illustrating side effects of LTBI medications and visually indicating they should call the clinic if they experienced any side effects.

Another potentially powerful support for adherence was the choice of treatment regimen. Although daily isoniazid for nine months was the standard regimen offered in our facilities, we offered four months of rifampin to our male patients, because they tended to leave the area in search of other work. We gave 9 months of isoniazid to our female patients, since many of them were also given oral contraceptives.

The deepening relationships between our staff, including interpreters and patients, were another important source of support for adherence to the workers’ LTBI medications. We made referrals for other health services for the patients and their families, especially children. Interpreters accompanied patients to other medical appointments, such as for chest x-rays. All these face-to-face visits afforded opportunities to address other psychosocial issues and to provide more education regarding TB treatment and other health topics. Over time the interaction increased their confidence to engage the health care system and empowered them to take more steps to improve their health.

Long-term Rewards

In the end, the overall completion rate for our LTBI patients was 62%, which was higher than the national average of 60%. We felt very proud of this result, particularly with a hard to reach population, and there were other long-term benefits.

The trust we established facilitated workers’ accessing other medical services, such as maternal-child health and hypertension screening, as well as the social services we introduced during treatment. The county health department was now seen as a trusted ally.

The experience also improved the already collegial bond within our health department team. Taking the collective decision to bring TB and LTBI services to the tomato packers, brainstorming about implementing the decision, adjusting our procedures as we went along, and congratulating each other as we achieved each step strengthened trust and communication. By the end, we were confident we could address any public health challenge in our community as a team.

We also identified new collaborative resources in the community, such as our interpreters. The interpreters went beyond helping us break through language barriers, and acted as cultural informants, illuminating aspects of our patients’ lives and backgrounds we would not otherwise have understood. Many patients we treated later promoted our services to friends and co-workers. The fire department has also become a partner, collaborating with us in community education efforts.

Finally, we also gained insight into areas where our program could improve. While we had several dedicated Spanish interpreters, a Mixteco interpreter would have been ideal. After the outbreak, we initiated a focused search for a Mixteco interpreter.

We realized our staff training in cultural competency had not kept pace with the changing demographics in our area. We would have benefited from greater understanding of Mixteco cultural traditions and beliefs that may affect how care is received. Since fully responding to the needs of our patients requires close collaboration with other medical and social service providers in our area, we believe other agencies should be invited to participate in cultural diversity activities in order to enhance the quality of care of patients community-wide.

The Contact Investigation: From the Individual to the Community

The tomato packing plant was in a small municipality in our county. Walking through the plant, we saw the potential for TB transmission. Carmen typically stood near her co-workers in front of one of many conveyer belts as part of a long line of packers. The room had low ceilings and poor ventilation. All workers mingled in a small common eating area. In our initial meeting with the plant manager, we identified 200 people to be interviewed as potential contacts. We educated the manager about the potential for TB to spread and the need to identify and treat cases of LTBI in his workforce, and he lent us an empty office for interviews. We negotiated with him to get time slots for interviews that would minimize interruptions of the work day.

Most workers were recent immigrants from Latin America, many of them Mixteco like Carmen. We found additional interpreters to help conduct interviews. Non-Spanish speaking staff only communicated with patients with an interpreter. Several interviewees spoke no Spanish, so we used Language Line to access interpreters for Mixteco and other dialects.

We ultimately identified 160 contacts to evaluate for TB disease or infection. The TB program staff at the health department discussed how we would manage to administer and read TSTs on such a large group. Based on our familiarity with Mixteco immigrants and on the interviews we conducted, we believed the contacts would not complete TB skin testing if they had to miss work. As a group, they prioritized earning an income; in many cases, the money they sent back home supported families, schools, village water systems and road work. Furthermore, many had little experience with health care systems, relying instead on traditional methods, so were unlikely to seek out services. We felt we could best reach our contacts and minimize loss to follow-up and work disruption by offering TSTs during lunch and break times. Skin test reading would take place two days later during the same time. The plant manager was agreeable as long as our activities did not interfere with anyone’s work schedule.

Organizational Cultural Competence

While promoting cultural competence among individual clinical staff is certainly important, another necessary action is to assess organizational cultural competence. Without attention to organizational competence, individual staff members may find that their efforts to serve members of a particular group are undermined by organizational policies and practices.

As part of their work on the Ad Hoc Committee of the Association of University Centers on Disabilities (AUCD) Multicultural Council, Hiranaka and colleagues (2004) developed an instrument (available at http://www.aucd.org/docs/councils/mcc/cultural_competency_assmt2004.pdf.) examining organizational cultural competence in seven areas. Below are sample assessment items from four domains - Organization, Administration, Clinical Services, and Research/Program Evaluation. The remaining domains are Technical Assistance/Consultation, Education/Training, and Community/Continuing Education.

Organization

- Cultural competence is included in the mission statement, policies, and procedure

- Partnerships with representatives of ethnic communities actively incorporate their knowledge and experience in organizational planning

Administration

- Personnel recruitment, hiring, and retention practices reflect the goal to achieve ethnic diversity and cultural competence

- Position descriptions and personnel performance measures include skills related to cultural competence

- Personnel are respected and supported for their desire to honor and participate in cultural celebrations

Clinical Services

- Translation and interpretation assistance is available and utilized when needed

- Pictures, posters, printed materials and toys reflect the culture and ethnic backgrounds of the consumers and families served

- The cultural and ethnic background of the consumer and family is considered when food is discussed or used in assessment or treatment

Research and Program Evaluation

- The researchers include members of the racial/ethnic groups to be studied and/or individuals who have acquired knowledge and skills to work with subjects from those specific groups

- Consumers and families representing diverse cultures provide input regarding the design, methods, and outcome measures of research and program evaluation projects

A similar self-assessment checklist can be found in the Global TB Institute’s Cultural Competency and Tuberculosis Care booklet, available at http://www.umdnj.edu/ntbcweb/products/tbculturalcompguide.htm

These materials can assist you in assessing your organization’s cultural competence. It is important to learn which cultural groups are prominent in your region. Finally, you should know what resources you have access to, such as interpreters and educational materials, in advance of an outbreak or other circumstances which may draw upon these resources.

Resources

Prevention and Control of Tuberculosis in Migrant Farm Workers: Recommendations of the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports, June 6, 1992 (RR10) http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00032773.htm

National Center for Farmworker Health (NCFH) provides information about farmworker health and services and products available for farmworkers throughout the US. http://www.ncfh.org

The goal of the Migrant Clinician’s Network is to improve health care for migrants by providing support, technical assistance, and professional development to clinicians in Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and other healthcare delivery sites with the ultimate purpose of providing quality health care that increases access and reduces disparities for migrant farmworkers and other mobile underserved populations: http://www.migrantclinician.org/

Let Us Highlight your Case

Have you, or a colleague faced a TB case that was challenging due to your patient's cultural beliefs or practices being dissimilar from your own? Have you experienced success in a case because you changed your typical approach based on something you learned about the patient's culture? If so, we'd love to highlight your case in an upcoming issue. Don't worry about producing a polished piece – we do most of the work! Please contact Jennifer at campbejk@umdnj.edu if you have some ideas.